In contemporary bio-philosophical theories, the concept of life is no longer articulated in the traditional way, with a central place reserved for individual beings. Instead, life is viewed through the lens of coexistence, where living beings are symbiotically connected, and the boundaries between them are blurred. The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19 is one of many confirmations of these theories, which reveal the fallacies of rigid boundaries between individuals. The primary method of protection against the virus proved to be the mask, which became a symbol of biopolitical adaptation to new circumstances. In her work, Karolina Żyniewicz focused precisely on this element of redesigning human presence, collecting used and discarded masks and archiving the biological traces of unknown people. She supplemented this archive of masks by systematically recording the life experiences of people she knew during the epidemic.

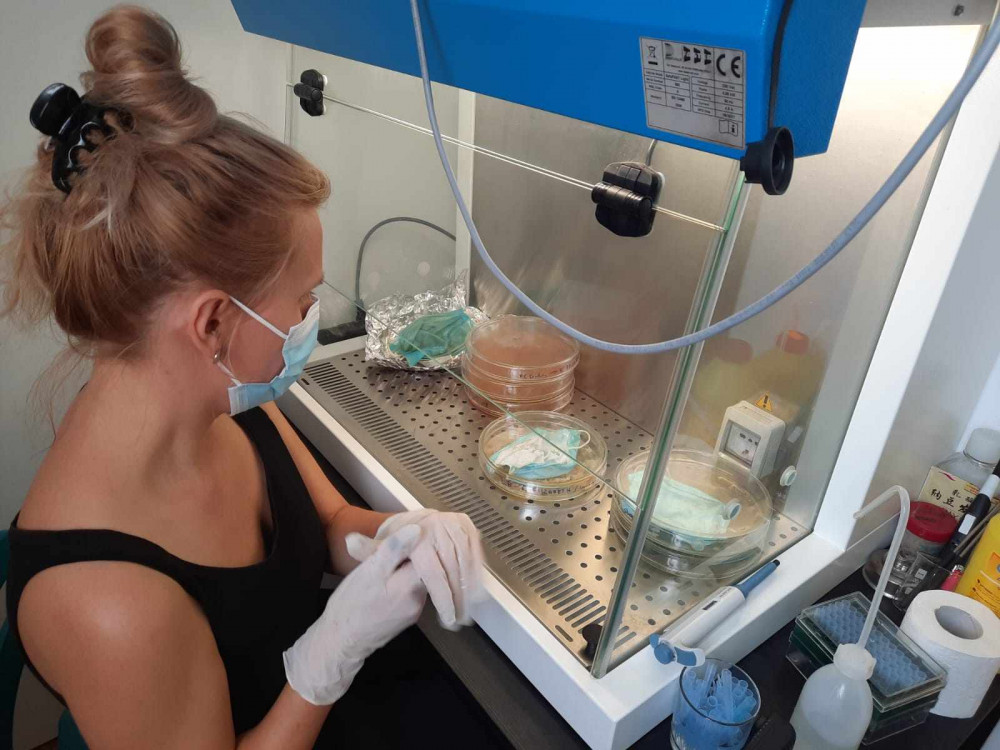

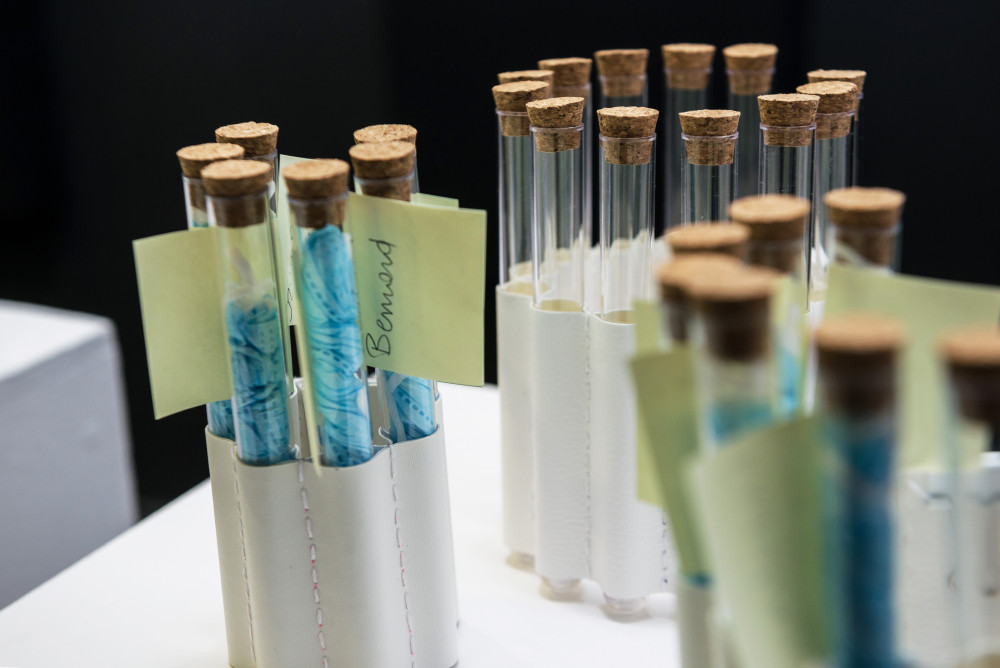

The COVID-19 pandemic is slowly fading from human memory, which is logical given that nearly four years have passed since the peak of the pandemic, marked by numerous deaths. To provoke necessary reflection on this topic, the artist transferred hibernating microorganisms from the archived masks into laboratory conditions, stimulating their growth and revealing numerous bacteria, fungi, and molds, some of which are pathogenic.

Żyniewicz also transmits others' experiences through her own body, performatively inscribing the archived memories. While the experiences of the pandemic unfold into stories on one screen, the genetic code of the microorganisms from the masks is simultaneously displayed on another. In this complex work, Żyniewicz explores the concepts of contamination and purity, as well as the social and biological boundaries that became blurred in the context of the global pandemic. The masks become carriers of memories and biological data, raising questions about the biological legacy we leave behind. Signs of the Times serves not only as a reminder of the fragility of human life but also as a means of resisting oblivion and alienation.

########################

In Dialogue: Artist Talk with Karolina Żyniewicz and Kontejner

Kontejner: In your work, you use discarded masks to explore the blurred boundaries between individuals and microorganisms. How do you see this symbiotic relationship influencing our understanding of identity and personal space post-pandemic?

Karolina Żyniewicz: I focus in my work on relations, interpersonal, and interspecies. It is crucial to me to stress that “I” should be replaced by “I-with”. The COVID-19 pandemic was a collective experience and a special occasion to investigate the notions of individuality and togetherness. On one side, we were encouraged to isolate and disconnect from others, on the other, we could not control microorganism structuring “I-with”. The mask worked as a symbolic shield, protecting us and other humans from uncontrolled virus exchange. We could imagine that everything behind our mask is pure “I”, but the microbiology tests I did in the lab showed evidence that “I” is only an illusion. It was not the unique “I” but a specific “I-with” construction.

Masks were worn for some time and then dumb as trash. It could be seen as a jump from protecting the illusion of “I” to accepting “I-with” and engaging it in broader entanglement. My project was designed to capture the friction between the vision of being one and only and the understanding that we are one of many. We function without masks again, but the swing between individualism and collectivism is invariably going on.

Kontejner: The concepts of contamination and purity are central to your work. How do these ideas resonate with the cultural and environmental issues we face today, and how do you hope your art will impact these discussions?

Karolina Żyniewicz: I agree that the notions of purity and dirt/contamination play a crucial role in my practice. They are also related to the category of abject, explored by me in the majority of my projects. I advocate for everything that we discard because of a specific cultural training. Continuing the thread from the previous question, I would say, that my goal is to encourage people to at least come closer to matter that they reject, to understand that it is a part of “I-with”. Many forms of discarded matter are perceived as dangerous because they question our anthropocentric concept of existence. The virus was a form of unwanted contamination because it caused the death of humans. Since we found a way to neutralize its influence on human life, it is accepted as an “I-with” component. The pandemic was a perfect situation to observe the current state of understanding the purity and danger. We wore a mask to stay “clean” and safe and then trashed them. In the first stage of the project, I was collecting masks from the streets, parks, and squares. They were everywhere, adding a new color to the landscape of the Anthropocene. It looked like they were symbols of purity being worn and physical evidence of danger being discarded in the environment. The laboratory examination of masks (collected in the city and given by specific mask and memory donors), showed an interesting dissonance. The masks were hygienic items, a barrier between bodies to reduce the spreading of the virus. We were so focused on the virus that we forgot about other micro “I-with” components. The lab experiments led to the discovery of pathogens on some mask samples. It means that being focused on the virus we forgot about micro agents that could be much more dangerous. The categories of purity and danger/contamination are fluent and dependent on the context, state of awareness, and decision about naming. My goal in the Signs of the Times project is to play with the fluency of these categories. I create a context, bring awareness, and encourage “I-withs” to experiment with naming.

Kontejner: Your art combines performative storytelling with scientific processes, such as growing microorganisms from masks. What do you hope audiences take away from the intersection of these two seemingly different methods of expression?

Karolina Żyniewicz: One of my inspirations for this project was the concept of “storied matter”, proposed by Opperman and Iovino. They suggested that every form of matter plots a story by its existence. As humans, we can try to decipher the stories of non-human and even non-living agents and translate them into human language. The task is easy with other humans, they can articulate their own stories. It is just a matter of listening and recording. It gets much more challenging when it comes to the other “I-with” components. Many people have asked me how I want to decipher the stories plotted by the microorganisms found on the masks. To answer the question we need to step out of our anthropocentric understanding of storytelling. We have done a transcription of “storied matter” when we discovered DNA and wrote the genomes as a combination of letters. The translation is partly done this way. We have letters that are components of every human language. We can read the genomes and get to know the specifics of the organism. This is just another foreign language to learn. Why does putting together the stories told by people and microorganisms' genomes seem strange? I would say that because we are squared in our anthropocentric vision. We learn other human languages because we find it useful to communicate with other humans. How many of us are interested in learning the language of “storied matter” of non-humans?

Kontejner: As an artist working at the crossroads of biotechnology, medicine, and ethnography, how do you balance the scientific and emotional/cultural aspects of your work, and how do you envision this interdisciplinary approach shaping the future of art?

Karolina Żyniewicz: I call myself a liminal being because I exist in between disciplines, fields, and topics. This is not a calculated strategy, it is simply the way I live. The decisions about the sources of knowledge and experiences in my projects are dictated by my life trajectories. When I want to explore something, it does not matter to me what kind of label is put on the source of the experience. The most important aspect of my work is my full embodied engagement in the project, authenticity, and honesty. These features help me to collaborate with scientists, engineers, and other specialists. I believe in simplicity of relations with human and non-human others, built on respect, and care. The research processes can look very complex but I like it when their outcomes trigger simple emotions and bring reflection. The emotional component is something I miss in many cases of art&science production nowadays. Some artworks amaze the viewers with the use of cutting-edge technologies, they are entertaining gadgets that do not make me feel anything. I do not feel invited to the relationship with the authors. This tendency bothers me a bit. I hope that the new forms of art, transdisciplinary, interdisciplinary, hybrid, following the development of technology, will not lose the reflective and emotional aspect.

Kontejner: Why do you believe working with memory is important in your art, and how does the COVID-19 pandemic serve as an example to explain your approach to exploring memory and its ideological significance?

Karolina Żyniewicz: Signs of the Times is the first project in which I directly address the topic of memory. In my PhD research, I worked with the notions of matter, mattering and transmattering, understanding matter as a physical being, meaning and importance, in constant transformation. The Covid-19 pandemic was a perfect context for continuing this research. Memory is routed in an embodied, physical experience. Mattering of the memory happens in our brain, where we are giving a certain importance to the experience. Transmattering happens when we articulate the story about the experience, using human language. In my project, I added more layers of transmattering by recording the stories and transcribing them, according to what I heard and using them in the installation. The beauty of memories is that they are decomposed by time. I used to work a lot with decomposing physical matter, trying to preserve it, and agreeing that I would lose in competition with time and natural processes. The same happens in the case of the Signs of the Times installation. I do a Sisyphean work writing the transmattered memories down, and they keep disappearing. A similar process happens in the case of the micro elements of “I-with” from the masks. They are given growing media to live, but they die after some time anyway. The persistent will to have something for sure and forever is mixed with the acceptance that it is impossible. The pandemic seemed to be such a strong experience that we will never forget but keep doing it. The matter remains changing.