Marleine van der Werf is a filmmaker and visual artist with a documentary practice based in Rotterdam (NL). In her artistic research she explores how to immerse in someone else's experience. Through cinema, virtual reality and multi-sensory technology Van der Werf creates haptic experiences to challenge the understanding of the other and the self. Recurrent themes are embodiment, identity and the perception of reality.

Antoine Bertin is an artist working at the intersection of science and sensory immersion, field recording and sound storytelling, data and music composition. His creations take the form of listening experiences, sound sculptures and audio meditations on the realm of the living. His work has been presented at Tate Britain, at the Palais de Tokyo, at the Serpentine Gallery, KIKK, STRP, Sonar+D festivals and more. He produces a quarterly show called “Edge of the forest” on NTS Radio.

###################################

In Dialogue: Artist Talk with Peter Zorn (Werkleitz, Halle):

Peter Zorn: Your work Disembodied deals with Cotard Syndrome, a disease that gives people the feeling that they are no longer part of their body. How did you come to this topic?

Marleine van der Werf: When I was a child I saw from up close how it is to loose your mind and I always thought that ‘owning a body’ is one of the few certainties we have as humans. But when I read The Disembodied Lady by neurologist Oliver Sacks combined with new research on exoskeletons, uploading consciousness and artificial intelligence I started to question the connection to our body. This sparked my artistic research in the domains of body ownership and the boundaries of our self the last few years.

After seeing what it is to lose one’s mind, maintaining the connection to my body became a way to survive. In that sense, Cotard Syndrome embodies my greatest fear. The aim of this project however is not to create a sensa¬tional or horrific experience. But to learn from people who suffer from it and to invite the spectator to reflect on their own relationship with their body. Given Covid, rapid digitaliza¬tion and robotization, Disembodied invites us to consider what ‘we’ are and what our bodies mean to us.

Peter Zorn: Disembodied is a multi-sensorial project, for which artistic formats and expressions did you decide and why?

Marleine van der Werf: This multi-disciplinary project is an intimate journey in which the fragile relationship with our biological body is questioned. The ‘story’ is based on experiences of Cotard patients. A rare condition in which the affected person holds the belief that they have no body or do not exist. To create the experience we research and collect as many different stories as we can. Since it is a rare syndrome this is a difficult task, because it has not been documented as well as other syndromes. For the project we build an archive of these sensory experiences of these stories. Besides the knowledge we gain from people that have cotard experience and their doctors we integrate knowledge on disembodiment through the collaboration with other experts like neuroscientists, psychologists, philosophers, physicians and choreographers.

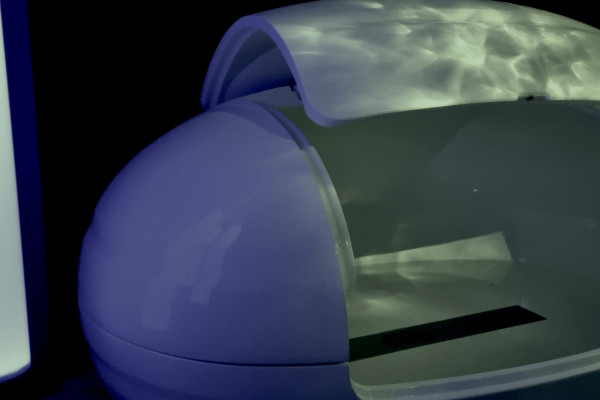

The Disembodied project is situated at the intersection of these different disciplines and, based on its investigative nature, researches ways to represent this disembodied experience in a diverse range of presentation forms. For example a documentary film, a virtual reality experience combined with wearables and a sensory-deprivation tank. Every medium uses another aspect of our research; the film will give voice to the people that have cotard syndrome and gives insight into exploration of the physicians and scientists that believe this syndrome unlocks the mysteries of where our consciousness is located. The Virtual reality experience and sensory deprivation tank will invite the participants body to engage with it. One of the findings during our research was while interviewing writer Esmée Weijun Wang in collaboration with dancers from the Motus Mori. Esmée has cotard syndrome and the feeling that her arm wasn’t her arm anymore. One of the presentation forms will be a sensory deprivation tank. In which you float in darkness and the warmth of the water is exactly the same as the outer skin. Which makes you question where your body begins or end. During the research we test different artistic and scientific methods to create these sensations.

Peter Zorn: How does your research process during the residency go?

Marleine van der Werf: Before the residency started I collected stories, audio, filmfragments and different experiences of cotard syndrome and disembodiment. So during the residency I want to organise and translate this archive in concrete artistic presentation forms and short films/ audiovisual installations. I aim to visit local experts in the fields Haptics; the Haptic Research Laboratory and make connections to production companies that create VR-experiences.

During the residency in Werkleitz I plan to create two experiments with participants to develop the presentation form in a sensory deprivation tank further. In the second week of the residency, I presented a first experiment at the Literaturhaus in Halle (Saale). In which we tested the script and sounddesign in an immersive audio experience of 10 minutes. In this experiment I collaborated with sound artist Antoine Bertin and researched different sensory components to understand how this influences the experience of the participant / spectator. And how it influences the on and off boarding. To collect these finding I did short 1 on 1 interview with the participants that I will analyse with Assistant Professor Desiree Foërster at the department of Media and Culture Studies in the cluster Media, Arts & Performance at Utrecht University.

Together with Antoine Bertin we will create a new experiment during the Transmediale in Berlin. We plan to rewrite the narrative experience and create a prototype of the installation in a sensory deprivation tank. This means a constant interaction between the participant and the project being an on-going research process.

Peter Zorn: How do you convey complex scientific statements in your work?

Marleine van der Werf: By working closely with different people that have experienced these complex situations themselves and find ways to make this tangible. For me it is not so much about the statement, but more about questioning. This is why I became a filmmaker, to discover what I can learn from people who have a radically different perception of reality than me. To break free from my comfort zone and broaden my frame of reference. For me as a queer woman it can be quite uncomfortable to interview someone who says all queers will go to hell, because that is what their religion states. But unless we enter into a dialogue, nothing will change. We need to think of what connects us, instead of what divides us. It also means challenging one’s own, my own, assumptions when making a film about, say, people who feel disembodied. What can we learn from each other’s perspective?

This is similar with other domains than film or art practice. I collaborate often with scientists that research the same questions that I have and do experiments to understand the same questions. We can learn a lot from different disciplines and sharing these methods and findings is really important to generate new knowledge. It showed me that different disciplines can have similar starting points and thought processes and that they differ only in the outcomes and the way they present these outcomes.

Peter Zorn: What are your experiences of working in the documentary film scene and the (media) art scene? What differences do you see?

Marleine van der Werf: I have been working as a documentary filmmaker and visual artist since 2010. But most of the time these ‘worlds’ were quite seperate. The multi-sensory installation I showed during File festival in Sao Paulo would not be shown at a documentary filmfestival. But the last few years this has been shifting, which I think is great. As a filmmaker the only interaction with the spectator I had was during the end of a project, mainly after the screening or in a Q&A session. But this is of course limited, because by that time you’re often already working on other projects. This means that the information about the experience of the spectator or participants gets lost in the creative process. Now, rather than waiting until the premiere of the film or installation, I create prototypes earlier in the process, which I test with participants. I use the outcomes of those experiments to further develop the project. This means I am in constant interaction with the spectator with the project being an ongoing research process. This changes also the way I structure my practice. I now concentrate less on the answers or the end product. Instead, I keep asking questions throughout the entire process and make different presentation forms that correspond with the artistic research. This stimulates curiosity and in depth conversations in which we discover much more in a playful manner.